Advancing Access to Legal Remedy: Eliminating Racism in the Legal System through Collaboration and Technology

By Ian McDougall

The Rule of Law

Access to Legal Remedy is one of the four pillars of the LexisNexis Legal & Professional definition of the Rule of Law. It describes the ability of any person to use the legal system to get redress for legal grievances, to advocate for themselves and their interests. Yet because of systemic bias in the legal system, access to remedy is still unavailable to many people from diverse backgrounds.

The United States criminal justice system is the largest in the world and, as written, U.S. law is essentially color-blind. But despite federal laws intended to provide equal access, systemic racism continues to persist throughout the judicial system. This has led to devastating social and economic consequences for individuals from diverse backgrounds. African Americans are incarcerated in state prisons at five times the rate of whites; black men face disproportionately harsh incarceration experiences compared with prisoners of other races; higher rates of incarceration for black juveniles reinforce the school-to-prison pipeline.

These issues are underscored by the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2020, which in its civil justice category ranked the U.S. at just 109 out of 128 countries in terms of access to justice and 115 out of 128 in terms of absence of discrimination.

Complex but interlinked circumstances contribute to this seemingly self-perpetuating state of affairs, including socioeconomic inequalities, lack of diversity in the legal profession, and conscious or inadvertent bias.

Federal legislative changes have been introduced with the goal of supporting individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds. However, these changes have not yet had much of an impact for two main reasons: a communications gap between the federal legislature and the individuals they are designed to help, and a lack of resources for impacted individuals.

Given the persistence of these problems, it’s clear that top-down attempts to make a difference are not sufficient in themselves. We also need initiatives that bridge existing gaps by addressing issues at the grassroots level. To maximize their effectiveness, these initiatives should combine community, legal, and technology perspectives. Such programs can build on existing innovations – such as the free app Upsolve, which helps people file for bankruptcy on their own – or use legal databases as the foundation for developing tools, training, and information that will increase the opportunity to remedy any grievance.

"It's clear that top-down attempts to make a difference are not sufficient in themselves"

What's the Solution?

There’s no single magic bullet. It takes multiple steps and many different, practical actions to eliminate any systemic problem. While one project on its own can’t alter the status quo, the legal profession can build real momentum and achieve lasting change by collaborating with cohort groups and other industry players to address some of the smaller, everyday examples of inadvertent racism. Whatever shape these projects ultimately take, it is essential they be based on reliable data rather than opinion or unproven assumptions. Data must be sourced from practitioners working with people of diverse backgrounds, ranging from disadvantaged individuals who have struggled with the court system to judges who have ruled on related cases.

With the goal of effecting meaningful, incremental change, a new fellowship program has been created by the LexisNexis Rule of Law Foundation (LNROLF) in partnership with the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Law School Consortium (HBCULSC) and the African Ancestry Network (AAN) – an Employee Resource Group within LexisNexis Legal & Professional (LNLP). The AAN/LNROLF Fellowship is part of an ongoing commitment by LexisNexis to work towards eliminating systemic racism in the law. Twelve recipients, consisting of law students from the HBCULSC Law Schools, including Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University College of Law, Howard University School of Law, North Carolina Central University School of Law, Southern University Law Center, Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University, and the University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law, have been awarded fellowships to identify the underlying causes of systemic racism in the legal industry and develop a set of pragmatic solutions that can work together to combat it.

We believe law and technology, combined with mentorship and collaborative support, will be instrumental in bringing better solutions to the industry more quickly. Law students who have a passion for making change but who don’t know how to build an app or fine-tune data modeling will have an opportunity to work directly with data scientists and software engineers. Fellows can tap into a global corporate network to exchange ideas across multiple countries.

"Fellows can tap into a global corporate network to exchange ideas across multiple countries. "

The fellowship program is also notable because of its focus on multiple issues and their interrelationships rather than a single aspect of the problem. Each fellow is tackling a separate issue and working to develop tangible, tech-based solutions that will make a difference in specific areas of the law. At the same time, fellows will be working collectively to build an interconnected set of initiatives that impact the larger goal. Project focuses include judicial bias, pro se litigant challenges, consumer bankruptcy issues, and other diverse but interrelated problems.

“The first step towards taking practical action,” says Feven Yohannes of Howard University School of Law and a 2021 AAN/LNROLF Fellow, “is understanding what aspects of the way clients present themselves in legal situations contribute to the disconnect between people of diverse backgrounds and the law. The path to inequality injustice starts at a very basic societal level and is seen with issues like underfunded schools creating a known school-to-prison pipeline, the hyper-sexualization of black girls, youths of color being followed in stores, and many others. These spillover into preconceptions in the judicial system based on color rather than the facts of law.”

Yohannes’ project seeks to identify and quantify levels of judicial bias in specific districts with the help of data analysts who can analyze trends and detect statistically significant patterns. The data scientists’ expertise, which has allowed her to access new insights by narrowing data and controlling for certain issues, has been a powerful boost to her research. She is supplementing her data-based research with in-person conversations with judges and analysts to compile anonymized demographic data. Although Yohannes is still in the data collection process, her ultimate goal is to create an online anti-bias judicial training program that incorporates recommendations for best practices based on her research findings.

Yohannes’ research focus is supported by numerous papers, including a 2016 study from Stanford University which concludes that effectively defusing discrimination starts with determining whether people believe racial bias to be intentional or unintentional. If individuals believe that discrimination reflects intentional racism on their part, the study found, they are more likely to try to behave in a “colorblind” way. Her research also builds on findings in a 2018 report to the United Nations on racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system, which noted that, while it is difficult to eradicate racial bias at the individual level, training can play an important role in reducing the problem. Studies have repeatedly shown that it is possible to train individuals to be behaviorally unbiased despite any beliefs they may privately hold.

While speaking to judges about the topic can be sensitive, Yohannes says, “It’s proving helpful to speak with actual legal practitioners to ensure they’re cognizant of the issue of judicial bias. Our discussions allow us to find out in what circumstances their advisement might be unconsciously skewed to suggest white clients act differently from black clients – for example, is it based on how they are paid, how articulate their clients appear to be, or their perception of how clients will fare?”

Failures in self-representation

Judicial policies consistently impact disadvantaged groups adversely. This inconsistency has led to some individuals attempting to represent themselves, and most failing to do so adequately. In some instances, defendants may not trust attorneys, they might not be able to afford representation, or they can’t get help from overstretched indigent defense resources. All too frequently, self-representation works against them.

Multiple studies show the hardships people of color face after being convicted of low-level crimes. These poor outcomes contribute to an ongoing distrust of the court system and a self-perpetuating cycle of judicial inadequacy. People with criminal records face a host of barriers to re-entering society after they have completed a jail term or period of community supervision. Obstacles include difficulties in securing employment, renting or buying property, accessing federal student aid, obtaining professional licenses, or even voting.

These overarching disadvantages are currently not addressed by practical solutions. Oscar Draughn, another 2021 AAN/LNROLF Fellow and student at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University College of Law, is developing a digital app that will give people who are charged with misdemeanor offences and are not represented by counsel better insight into the court process. Defendants will have access to practical information ranging from when they need to appear to the specific consequences of the decisions they make before, during, and after their court appearance.

“Self-defenders get basic information from court clerks that they don’t understand and, whether it’s through choice or lack of means, they don’t have access to legal advice to help them go through the process successfully,” he explains. “The goal is to not create the tool based on what I or other legal professionals think this group needs, but to make it relevant by getting real-life input from individuals who have gone through this process and better educate people to help themselves.”

Draughn acknowledges the app can’t solve the problem of self-representation entirely, but he says it can contribute to a reduction in the prevalence of poor outcomes and combine with other projects to make a substantial difference to the effect of systemic racial bias. The new pro se litigant resources app will include a knowledge database, step-by-step tutorials, and interactive modules that can be accessed by a computer or mobile device. The tool will minimize the probability of conviction for reasons unconnected with the facts of the case, such as unfamiliarity with legal procedures or missed deadlines. Fundamentally, it is a resource to help prevent defendants who are charged with minor offenses from being convicted and labeled as criminals.

There’s a clear connection between the participation of large technology developers and the pace of progress in building facts and creating digital tools that can actively solve grassroots issues. A vital element, Draughn says, is not just creating useful technology, but making sure that innovations also factor in the digital divide by offering print versions of relevant materials to individuals who lack convenient access to computers and smartphones. “Technology developers need to ensure that the applications and materials they create are not biased in how they serve others,” he observes.

Draughn is enthusiastic about the growing involvement of larger technology companies on these projects. “It opens opportunities for worldwide collaboration. Working with a global company gives you access to other individuals and different perspectives and being able to leverage very large databases allows you to progress projects far more rapidly.”

Consumer Bankruptcy Toolkit/Filing Checklists

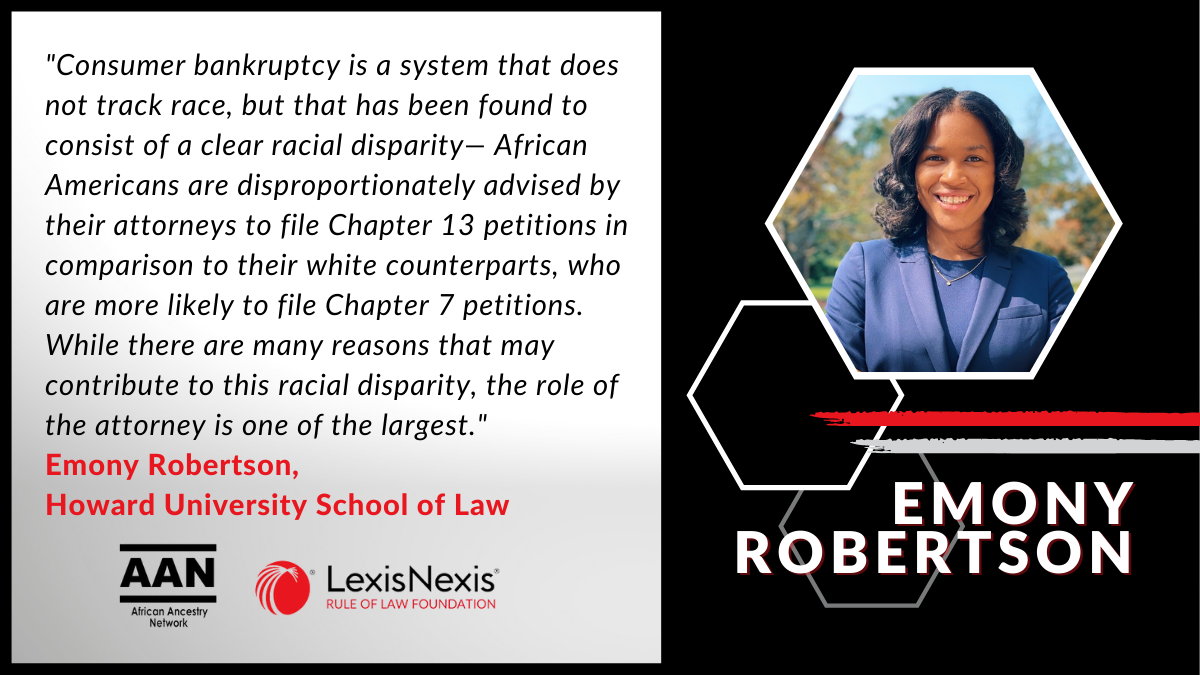

Various studies indicate that people of color struggling with debt are far less likely than their white peers to gain lasting relief from bankruptcy. Under federal bankruptcy law, people overwhelmed by debt have a choice of filing under Chapter 7 or Chapter 13. Chapter 7 wipes out debts and allows filers to keep property not secured under bankruptcy exemptions. Under Chapter 13, five years of payments to creditors are required before any debts are eliminated, but foreclosures and car repossessions are also blocked so long as debtors can keep up with their repayment plan. In most of the country, Chapter 7 is the overwhelming choice but there’s a history of African American clients being directed toward Chapter 13, which doesn’t protect debtors if payments are not made.

The problem with Chapter 13 is that once the bankruptcy period has ended, the debt floods back larger than ever. Filers of Chapter 13 must bear the costs and conditions of bankruptcy including a seven-year flag on their credit reports, but instead of being able to eliminate debt they end up with more. Studies focused on racial disparities in the consumer bankruptcy system have found that African Americans make up a higher percentage of debtors across the bankruptcy system compared with the total population.

Emony Robertson of Howard University School of Law, also a 2021 AAN/LNROLF Fellow, is working to determine the feasibility of a new consumer bankruptcy toolkit for practitioners, judges and academicians that would help them improve outcomes for African Americans through conscious practice. Robertson is reaching out to consumer bankruptcy practitioners to understand their current advisements and discover whether new or updated tools will be helpful in avoiding bias.

“While you can’t identify race by examining data from bankruptcy procedures, some of the information on file makes assumptions based specifically on race,” she says. “It’s difficult for practitioners to acknowledge bias and the need for change, but there are small ways in which they can be encouraged to change via adjustments to the tools they use. It’s important for tools to be built from an approach of equity. This project may result in reframing or recrafting some database tools, although it’s too early in the process to be precise about the outcome.”

One goal, Multi-Faceted Approaches

There is no single path to achieving the goal of eliminating racism in the legal system but by taking a multi-faceted approach targeting specific areas of improvement can and will drive a faster pace of change. New initiatives such as developing technologies to assist legal professionals and their clients, fostering diverse talent by providing mentorships, scholarships, and internships, and creating organizational policies that engage people from diverse backgrounds in technology development will go a long way to winning the battle against bias.

Eliminating systemic racism in the legal industry will require multiple changes across the entire system. High schools, law schools, law firms, and technology developers must all recognize that investment in diverse individuals cannot be a one-time, feel-good donation. It requires a commitment that spans years and extends across the entire spectrum of legal practice. Small adjustments, training, technology, and collaboration have the combined power to take down the barriers that prop up systemic racism once and for all.

Want to read more on the LexisNexis Fellowship projects?

About the Author

Ian McDougall is the Executive Vice President and General Counsel for the LexisNexis, Legal & Professional division of RELX Group. He is also President of the LexisNexis Rule of Law Foundation, a non-profit charitable organization established to advance the Rule of Law. Ian sits on the United Nations Rule of Law Steering Committee and is a member of the UN General Counsel Advisory Board.